| |

Home

Thousands of tastings,

all the ramblings

and all the fun

(hopefully!)

Whiskyfun.com

Guaranteed ad-free

copyright 2002-2026

|

|

|

| Hi, this is one of our (almost) daily tastings. Santé! |

| |

|

| |

| |

January 1, 2026 |

|

|

On the agenda this New Year’s Day: our official New Year’s wishes – probably the daftest we’ve ever come up with, but don’t worry, next year’s will be even worse – followed by the first instalment of a superb three-part article by Angus on whisky and terroir. And finally, two cracking little Springbanks to kick off the year in style. Sound good? In the coming days, you may expect our 'best' of 2025 and maybe some funny figures. Stay tuned. |

|

|

Angus's Corner

From our correspondent and skilled taster Angus MacRaild in Scotland

Illustrations, Serge's son, whose artist name is Darius Pronowski |

|

|

In March this year, we took a family holiday to Orkney. That trip, along with a number of contemporaneous occurrences and discussions in the whisky industry at that time (and now), motivated me to write this piece. I finished it this past week and it’s quite long, so I’ve divided it into three sections and published it here on Whiskyfun during the holidays. I hope you like it. |

|

|

Whisky and terroir:

Part One |

|

Scotland’s edges appear ragged and torn, framed by the weathered scars of ancient and violent geology. Approaching from the softer innards of Fife and Perthshire, the land sparsens and tenses; you get a sense of Earth’s sinew and bone yearning against the membrane of landscape. Geological desire lines of rock, insisting their way to the surface, to exposure and light. |

|

|

We drove the crooked spine of the A9 and A99 all the way to Gill’s Bay; beyond Inverness, through relentless Spring sunlight, everything was yellow splashes of Gorse facing the dazzling, ever-shifting blue of the North Sea. Broken up by fields of compelling green and the deeper greens of pine. As we pass Golspie, Brora and Helmsdale, those greens begin to mottle, phasing into peat and moorland, the Gorse yellows become intermittent, and a sense emerges of exposure and rawness. The land appears beaten, winnowed into low oppression by ancient channels of wind. Trees are fewer here, clustered into sheltered dips and furrows of the earth, those that grow in the open have yielded to the shape and will of the same winds that have raked this land since it was molten. |

|

|

The shape of the language changes here too – Latheron, Lybster, Clythe, Thrumster – funny words without the romance or lyricism which we usually associate with the Scottish Highlands. Words that give a sense of older and different cultures, that speak something of the strangeness and starkness of the land they stand for. At Gill’s Bay the ferry breaks away from the exposed rock and strikes out towards Orkney. In this light the sea appears a vast and open plateau of quiet, sun-enriched blue, an expansive, modulating blue that plays with your vision and can change the way you think about an individual colour. The calm of the water is surreal; we’re aware that we drift across a resting beast capable of the almightiest fury. |

|

|

|

|

|

Orkney emerges out of this unsettling blue surrealism: green and lolloping fields stitched between peatlands with drystone seams and smudges of mottled rock. It feels, in the immediate sense, like another world. Like so much of northern Scotland, however, amidst all this surface beauty and a serenity temporarily granted by the grace of Spring sunlight, it is possible to sense an emptiness, the disquiet of emptied lands – of a culture and people not so long ago decanted away to make space for sheep. Go to Lewis and the shape of the land might tell of a different geology, a different accent to the beauty, but the quiet absence is the same. |

|

|

Spend a little more time, and everything becomes more cosmic and amusing: this is a land that eats everything! All we can do thus far, in the face of this slow digestion, is put up rocks. We can order them simply or with artifice and grandeur, but the entropy of the wind, the lichen and the bog at our feet make a mockery of it all in the end. You can feel these things on mainland Scotland, but on Orkney – the cradle of civilization in these British Isles – these things feel a little starker, a little more exposed and inescapable. It is a humbling place to be. It's also a place where it’s possible to feel ever so slightly more at ease with this ruthless impermanence. |

|

|

As I write this, I’m drinking a Highland Park single malt. It is ten years old, distilled in 1999 and aged in a first-fill bourbon barrel. Its flavour makes me think of honey, it recalls heather and the sense of peat smoke somewhere in the background. It is sweet, but naturally so. I wonder if this distillate was tankered off the island to be filled and mature in a warehouse somewhere in central Scotland; is this the first time this (now) whisky has been back to Orkney since it was spirit off the still? Knowing a bit about whisky, you wonder these things. But these supposedly dissonant thoughts sit in odd comfort alongside drinking this whisky and thinking about flavours I associate with this land and this place: honey, heather, peat, coastal air… |

|

|

|

|

|

On the journey up here, we stopped at Dornoch Castle for a night, a place I’ve tasted many of the whiskies made at the distilleries that dot the land we just travelled through. Pulteney and Balblair feel like sibling makes to me: sweeter, more bucolic distillates that inhabit the space between those yellow flushes of gorse and iridescent coastal blues. Clynelish, Ord and Dalmore feel like they belong to the more austere, exposed and stony parts of these lands, in my mind these are more muscular and weighty spirits, mineral, like the exposed, wind-hewn geology they sit upon. |

|

|

To write about Scotland, and about its whiskies, in the way I just have is a choice. It’s a style frequented many times over the years by any number of writers. It’s a way of writing that tries desperately to be unromantic but fails nobly. There is probably good reason why we write this way, why we knit together the land and the whiskies that are made within and upon it, there is an instinctual urge to use the former to make sense of the latter, to use that awe-inspiring landscape as a narrative canvass in which to figuratively contextualise the whiskies that are literally made there. By the same token, there is a common and highly deliberate urge to uncouple these things – to drive the wedge of science and rationality between the land and the distillates and to rend them apart. |

|

|

This is the argument that we’ve been having for at least three decades now: the argument about terroir, about whether it exists in Scotch whisky, and if so, to what extent? How do we discern it? How do we refute it? I have been continually fascinated by the conversation, but I haven’t written much about it myself. The recent misfortunes that have befallen Waterford in Ireland, and this holiday I’ve taken to Orkney, have both made me think once again about terroir and its place in whisky. I believe that, amidst all the bluster that swirls about this subject, what is missed is not if terroir exists in whisky, or if it can exist, but whether terroir matters at all? If it does matter, then why? I do not intend to fully litigate the case for or against terroir’s existence in whisky, although, there will need to be some discussion of this, and I should say, in my view, terroir can and does exist in some spirits. What I believe is more interesting is why we discuss terroir in whisky at all… |

|

|

|

|

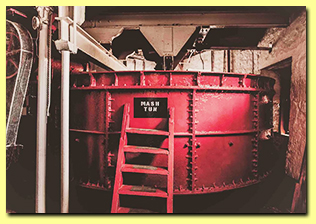

Time Warp: Springbank ex-sherry by Signatory, 20 years apart |

You understand, we just couldn't let these final festive days pass without enjoying a bit more Springbank, could we? So we gave some serious thought to what kind of duo we could put together, and in the end decided to taste two Signatory Vintage expressions distilled twenty years apart. Which, let’s be honest, makes as much sense as any other setup. We needed a theme, you see… |

Isn't it said that the best soup comes from an old pot? |

|

Springbank 35 yo 1989/2024 (47.8%, Signatory Vintage, Symington’s Choice, refill oloroso sherry butt, cask #14/03/1, 345 bottles)

The last Springbank 1989 from Signatory we tasted had been bottled back in the year 2000, imagine that! Colour: deep amber. Nose: full-on rum-soaked chocolate and raisins at first, and that goes on for quite a while before notes of petrol and shoe polish start to sneak in, together with fresh plaster, all adding that proverbial ‘Springbankness’. Then come dried apricots and a few wisps of crème de menthe. Very lightly oaked for now, leaning more towards singed fir wood than anything else. Mouth: chocolate, fir wood and mint right from the outset, and the whole thing is almost as dry as a cane thrashing—not a flaw at all in this context. We’re soon heading toward dark tobacco and bitter chocolate, paired with clove and juniper, plus a slight touch of salted grapeseed oil—that’s pure Springbank. No sulphury notes, which one might have feared in this vintage, especially in a sherry version. Finish: long, saltier, with more of that very black tea, mint, and, believe it or not, a drop of mezcal. The famous Campbeltown agaves, aren’t they (just joking). Comments: of course it’s excellent, even if the sherry does take the upper hand a bit, slightly overshadowing the fabled distillate. But all things considered, we love it, naturally. Watch out though, competition is on the way…

SGP:462 - 90 points. |

|

Springbank 27 yo 1969/1997 (52.7%, Signatory Vintage, sherry butt, cask #2380, 520 bottles)

So many marvels in this series—Ardbeg, Laphroaig, and of course Springbank, some of whose 1969s have been absolutely magical (cask #790, WF 94) while others just a wee bit less so… But we hadn’t yet tasted this cask #2380, would you believe. Colour: gold. Good news! Nose: alright, let’s cut to the chase, this one is brimming with Springbankness, possibly a 3rd-fill. Sublime mineral and vegetal oils, chalky rock, dried banana peel, slightly underripe mangoes, tiny drops of peppermint essence, then a cavalcade of citrus peels, ointments, aromatic herbs, while—here comes a surprise—a wee oyster makes an appearance. Mad stuff. With water: little change, perhaps just a touch more greasiness—think engine grease—and a bit of paraffin. Mouth (neat): exceptionally oily and citrus-forward at first, then gradually shifts towards waxes, flinty notes, fruit skins (pear, peach, mango), and salted pistachio. Magnificent. With water: again, water doesn’t do much beyond gently amplifying the peppery and salty tones, and perhaps what the blessed younger whisky lovers, who’ve never seen James Brown live, refer to as ‘the funk’. Finish: long, more saline, more maritime, with our wee oyster making a comeback, joined by seaweed, nori, then grapefruit skins and pips. Beautiful bitterness. Comments: hardly a surprise, if we’re honest. Just between us, there are even faint echoes of ‘Old’ Clynelish, in sherry form.

SGP:562 - 93 points. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|