| |

Home

Thousands of tastings,

all the ramblings

and all the fun

(hopefully!)

Whiskyfun.com

Guaranteed ad-free

copyright 2002-2026

|

|

|

| Hi, this is one of our (almost) daily tastings. Santé! |

| |

|

| |

| |

January 2, 2026 |

|

|

|

Angus's Corner

From our correspondent and skilled taster Angus MacRaild in Scotland

Illustrations, Darius Pronowski

Whisky and terroir:

Part Two |

|

|

|

Terroir is a French concept, one evolved and nurtured over centuries. It describes the collective influence of soil, geology, climate, habitat and agricultural practice that collectively can be noticeably manifest in the final character of a product. Most commonly wine, but also other products as well. Terroir has also been argued to exist in people too, that regional characteristics related to the land and environment can be found in local populations as well. Finally, the most critical thing about terroir as it relates to French wine, is cumulative recognition and intellectual consensus arrived at over centuries of discussion and analysis. It is this latter point that Scotch Whisky lacks. We are just at the outset of that process in many ways, which is what makes our debates about this subject both healthy and necessary. |

|

|

I would characterise the modern ‘cultural’ era of whisky as aligning with the proliferation of the internet in the late 1990s. I would distinguish that from what we might define as a modern ‘production’ era, which is roughly from the early 1970s until today. In this modern cultural era, the people who pushed the discussion of terroir and made the case for it were Bruichladdich, chiefly Mark Reynier, who later further asserted this philosophy at Waterford. They were not the first people to talk about Scotch Whisky with language and ideas that alluded to concepts of terroir. Aeneas MacDonald’s book ‘Whisky’, published in 1930, expressed many viewpoints about Scotch Whisky which attributed its character to geographical influence. Indeed, this book is a fascinating artefact of an early, pre-modern era of specifically Scottish malt whisky enthusiasm. Malt whisky marketing from its fledgling era of the 1900s through to the 1980s, would frequently talk about water, glens, lochs, Highland air, Highland people, peat, tradition; things which are all potentially part of a much more formal definition of terroir. Ideas from wine were frequently repurposed for Scotch Whisky marketing, but rarely ever explicitly expressed. I remember being struck by the neck tag on an old 1970s bottle of Sherriff’s Bowmore that described it as ‘bone dry’ and ‘mineral’ – language very obviously re-purposed from wine. It was an approach which seems typical of Scotch Whisky: it would rather borrow and re-purpose, than create something bespoke. |

|

|

|

|

|

It was out of this world that Reynier and co took the next step and explicitly connected Scottish malt whisky with terroir. This was, at least in the initial phase, purely marketing, a way to speak about and sell a product which had been produced in a relatively unremarkable and traditional ‘modern’ manner with the destination of blended Scotch the intent. This is the most immediate ‘why’ of terroir in Scotch Whisky: a way to distinguish, to market and to sell a product that sets you apart from much larger, commercial competitors in a crowded marketplace. It is also one of the arguments that those who readily dismiss the existence of terroir in whisky reach for: it’s just marketing bullshit. It’s a useful argument as it reveals that, if you are going to talk about terroir, you’d better have something meaningful and demonstrable in your product and practice backing it up. |

|

|

Bruichladdich would go on, under Renier’s era, to make some valiant efforts in its production practices to shore up the terroir marketing angle. Under the ownership of Remy, Bruichladdich’s language has evolved and the explicitness around terroir has softened; focus on sustainability, provenance and ‘thought provocation’ have all been given equal or more prominent focus. Perhaps we can interpret this evolution as a quiet admission that such an intensely ideological focus on terroir is challenging to maintain to its logical conclusion. |

|

|

It is also often said that terroir is a choice, the wine grower can choose to step back and give it space, or she can choose to intervene to alter or delete its characteristics. It’s a tension between the natural effects of the land on a monoculture of vines and the judgement and human decision making of the wine grower. It is this idea of judgement and deliberate decision making that is most relevant and critical to Scotch Whisky as well. Terroir is bound up so deeply with French wine because it so often overlays effortlessly with the decisions which also lead to the greatest quality in the end product. The most lauded wines, also tend to vividly express terroir. In Scottish malt whisky production, can we say that the decision to pursue and allow room for terroir in the product are the same decisions that will lead to the finest possible quality whisky? I’m not convinced this is the case. |

|

|

|

|

|

When I was in Japan back in February, Yumi Yoshikawa at Chichibu made a very simple but important point: sometimes they use barley from Scotland, sometimes from Japan, but they don’t use Japanese barley for the sake of it as it isn’t always the best quality. They want the best quality barley for making whisky. A similar way to think about it might be a theoretical decision around what yeast strain to use. If you want to make a whisky that expresses terroir, you might want to isolate a unique yeast strain from your local barley, or from a peat bog you cut from, but will it make better whisky than using a more classical yeast? In whisky, terroir does not necessarily equal quality. |

|

|

So, does it follow that terroir in whisky is of less importance? That it belongs more to the remit of the marketeer and story spinners? I think it tells us that, if the whisky maker wants to legitimately discover, make space for and enshrine terroir in their product, then it must go hand in hand with quality as well. If you start a distillery with the foundational objective of expressing terroir, you will not really know the finer details of what character of whisky you’ll make, terroir is something that has to be discovered, then nurtured. Striking that balance while also navigating a pathway of decision making that elevates quality is a challenge. |

|

|

If done correctly though, it also conveys a potent message that goes beyond whisky and becomes political. True pursuit of terroir in whisky making is limiting, which means it limits the capacity of your business to endlessly expand and grow. To truly express character from your immediate and natural environment, means accepting limitations, it means standing apart from the mass commercial approach to whisky making that sacrifices quality in the pursuit of yield, efficiency and stretches credibility to breaking point on pricing. It says: I accept a different business model; I accept a certain limit to growth; I am pursuing commercial success via the route of quality and value - at the expense of volume. This is perhaps one of the most important reasons why terroir can matter, but it hinges on being done correctly with a rather dogmatic and ideological attention to detail. |

|

|

As soon as we interrogate terroir in whisky, it also throws up some challenging questions. What specifically is terroir in whisky, and how is it distinct from distillery character? For example, if you allow your site’s natural water resources to cool your distillate and you accept seasonal variation inherent in that, then is that character effect from cooling counted as a character of terroir or distillery character? If you chose to exert greater control over your distillate and you deploy technological means to maintain a uniform cooling profile all year round, does its effect transition from terroir characteristic to distillery character? |

|

|

|

|

|

One of the strongest arguments for the existence of terroir in whisky, is when peat is used. After all, what is peat but the literal, physical land? Land immolated and adhered at a molecular level into the very building blocks of the whisky itself. There have been studies that show there are geographical-specific peat flavour characteristics in Scottish malt whisky. Even when a distillery like Springbank uses peat cut from Tomintoul (as they have in recent times), it could be argued they are still expressing a terroir, just that of Tomintoul, not Machrihanish. This is one of the effects of the centralisation of malting, the reduction in diversity of peat bogs used, leads to a homogenising effect on peated Scottish malt whiskies more broadly. Following that logic, does the use of new, or relatively active, American and European oaks invest those spirits with some terroir characteristics of the forests of origin where those trees grew? In my view, the great contradiction that sat at the heart of Bruichladdich and Waterford, was their use of wine casks. If you make all that noise about terroir character and barley, only to then fill into active wine casks, the logical underpinning of your guiding philosophy falls apart. |

|

|

That’s the other political element of terroir. In the face of a climate crisis, and arguably a wider global ‘polycrisis’, the decisions that businesses take, and choose not to take, all carry meaning. If we can use an embrace of terroir to also make these sorts of luxury products, which make life enjoyable, more sustainable to produce, then this is broadly a good thing. It’s also a politically useful, even necessary, stance to have and one that will increasingly become essential in years to come. We turn our focus upon the natural and the local because we must and we should, but if it can also serve as a pathway to better products then this combination of purposes becomes one of the strongest answers as to why terroir can matter. |

|

|

|

|

|

WF's Little Duos,

today Banff vs Banff |

|

| (Banff and Macduff Heritage Trail) |

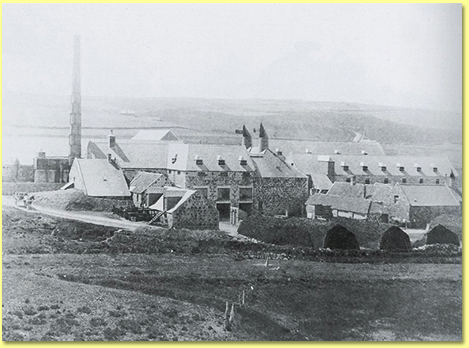

Another long-closed distillery we've always enjoyed tasting is Banff – admittedly rather inconsistent in style, as far as I can recall, but occasionally showing incredible flashes of fruity brilliance. It's worth remembering that Banff was closed in 1983, most of the buildings were demolished a few years later, and the last warehouse was destroyed by fire in 1991. A well-known story is that a Stuka had already destroyed part of the distillery in 1941, while an explosion during maintenance work destroyed a large section again, including the stills, in 1959. The final closure, however, was voluntary. |

|

Banff 1975/2013 (44.4%, The Face to Face Spirit Company, Jack Wiebers & Andrew Prezlow, bourbon cask)

These are extremely limited batches, sold exclusively direct to the punter, from time to time, especially at festivals. Yet another reason to turn up at whisky festivals, isn’t it? Colour: gold. Nose: and there you have it, mangoes and wee bananas rolled in vanilla cream, beeswax and a dab of olive oil, plus two or three fresh mint leaves tossed in for good measure. The result of this sort of combination is inevitably superlative, and one would never suspect this baby was 37 or 38 years old when bottled. For the time being, I find it clearly superior to the 1975 ‘The Cross Hill’ from the same source. Mouth: it’s a touch more on the oaky side, but that was to be expected, and the whole remains well in check thanks to the fruit, this time veering more towards apple and peach. The oak delivers cinnamon, allspice, aniseed, turmeric and nutmeg, plus a touch of white pepper, but it’s all reined in by the apple, which keeps the shop running. Finish: fairly long, with the spices still firing away from the oak department, a little more aniseed-driven now, while the wax and very ripe apple wrap it all up most elegantly. Comments: let’s say it plainly, these older distillates generally displayed more wax and fat than today’s malts ever dare to dream of. Superb Banff in any case.

SGP:651 - 91 points. |

|

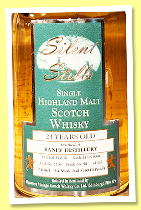

Banff 23 yo 1976/2000 (54.5%, Signatory Vintage, Silent Stills, cask #2250, 245 bottles)

A series that needs no further introduction really, and one we’re gradually working through with the thoroughness of civil servants on overtime. At this pace, I reckon we’ll have polished off the lot by around 2057. Colour: white wine. Nose: rather more on the rhubarb and kiwi side of things, with a faint metallic glint (old copper coins) and a touch of patchouli, quickly joined by mint, eucalyptus, and even fresh oregano and chervil, of all things. Fir honey wraps it all together—surely this one is properly ‘green’? Greetings to all smell-colour synaesthetes out there! With water: wax, honey, vanilla and figs enter the room. Mouth (neat): extremely close to the 1975 on the palate. Same fatness, same waxiness, same green fruits, angelica, apple... With water: perfect, with the return of mint and aniseed, backed up by the cask spices, still wonderfully elegant, with cinnamon at the helm. Finish: long, fatty, though lifted by citrus and dill. Comments: not all sister casks were from the same school, but 2249 by Signatory was superb, 2251 too. And so is 2250. A dead heat today.

SGP:651 - 91 points. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|