|

|

| Hi, you're in the Archives, January 2026 - Part 1 |

| |

| |

| |

January 14, 2026 |

|

|

Caol Ila in Utter Chaos, Part 1/4 |

You may already know this, but we love vertical tastings, especially by vintage, to track any changes in style over time. But we also really enjoy diving into large sessions in complete disorder — it's more fun that way. You just have to make sure not to start off with an absolute beast that could ruin the rest of your tasting. Oh, and take your time if you've got any. Here we go… |

(Caol Ila/Diageo) |

|

Caol Ila 14 yo 2011/2025 (58.7%, Best Dram, 1st fill red wine barrique, cask #900098, 279 bottles)

Entirely matured in a Bordeaux barrique, not just finished therein, which is worth noting, although the colour shows no salmon or rosé hues whatsoever, which is rather reassuring. Colour: let’s say light apricot. Nose: this is remarkably gentle, with pink peppercorns and assorted small red berries, all rather well-balanced, though at the cost of Caol Ila’s usual feral edge, already somewhat tamed in general, now rather dialled down. Some chalk, ashes, and oysters in raspberry jam—an experiment one ought to attempt someday, perhaps. With water: bruised strawberries on the ground, plus a few fresh rubbery notes. Mouth (neat): smoked and salted red fruits, say redcurrant jelly licked off burnt driftwood. The pink pepper returns, now with pink grapefruit thrown in, of the fleshy, bittersweet kind. With water: green pepper, pink pepper, and briny water. Finish: fairly long, though without any further evolution. Comments: really not bad at all, but it remains something of an oddity. A fine opener to kick off a session.

SGP:655 - 81 points. |

May as well go for a sister cask while we're at it... |

|

Caol Ila 14 yo 2011/2025 (53.5%, The Stillman’s De, 1st fill marsala, cask #900113, 290 bottles)

Marsala ought to be far less deviant than red Bordeaux, and indeed, that seems to be the case. Colour: full gold. Nose: the aromas of the Sicilian wine and those of the whisky are far more aligned here, or adjacent if you prefer, than in the previous configuration. Caol Ila comes through much purer, with crab, shellfish, ashes, sea water, and a trace of cigar tobacco trailing its own ashes. With water: a brand-new box of rubber bands and a handful of bitter almonds. Mouth (neat): excellent, with bitter oranges, lemon, sea water, ashes, greenish peat and tiny pickles in brine. With water: just lovely. Finish: very elegant too, with a faint touch of mustard. Comments: I’ve no idea if this was Grillo, thus a white Marsala, but it could well be. Not all are great, but from top houses like De Bartoli, Grillo can be utterly splendid. Just my two pence… In any case, in this rather particular context, it leaves the red wines in the dust.

SGP:566 - 87 points. |

|

Port Askaig 10 yo 2014/2025 (57.8%, Elixir Distillers, for Kirsch Import, toasted barrel, cask #1033)

It’s long been accepted that these Port Askaigs are Caol Ila in disguise, barring the very oldest ones, and nothing has come along to convince us otherwise so far. That said, peated Bunnahabhains could also be contenders. Colour: gold. Nose: rather rich and creamier than the previous ones, with banana, mastic, camphoraceous touches and seaweed dried on a sunny beach. We’re just waiting on the oysters now… With water: sauna oils and freshly sawn wood, a faint ‘IKEA note’, if you will. Mouth (neat): the banana’s back, some toastiness perhaps, then lashings of mustard and curry. The cask was seriously talkative. With water: it’s the wood calling the shots here. Finish: long, with paprika and more curry. Comments: oak is cool, but let’s not overdo it. That said, this one’s very, very, very good, of course.

SGP:575 - 84 points. |

|

Caol Ila 'Distillers Edition 2023' (43%, OB)

This one's never quite been our thing, and pairing Moscatel with Caol Ila remains something of an uphill task. Let’s press on, then… Colour: pale gold. Nose: you do get the muscat loud and clear, yet it doesn’t clash too much with the Islay side—here in a softer guise, leaning slightly towards mint. Mouth: vinous, but not bad at all, fairly fresh, muscat-laced indeed, aromatic and slightly sweet. Finish: pink grapefruit, lightly salted and peppered. Comments: really quite alright, even good in fact, though it’s not as if we’re short on other Caol Ilas.

SGP:555 - 81 points. |

|

Caol Ila 10 yo 2014/2024 ‘Edition #28’ (57.1%, Signatory Vintage, 100 proof, 1st fill & refill oloroso sherry butt)

A most commendable and ‘clever’ series from SigV. Colour: pale gold. Nose: I suspect the proportion of first fill was kept relatively low, and if that’s the case, so much the better, as everything remains wonderfully fresh, with overripe apples, soft leather, whelks and salmiak. Really lovely. With water: a touch of eucalyptus and medicinal notes, mercurochrome, and pink grapefruit peel. Mouth (neat): echoes of the official Cask Strength, as far as I recall, with green walnut, ashes, fine bitterness, seaweed and oysters. With water: elegantly chiselled peat, as they say, blended with lemon and bitter notes of the ‘Italian’ variety, not necessarily bright red, mind you. Finish: long, vibrant, fresh, peppery and peaty. No dissonance whatsoever. Comments: truly beautiful and admirably classic, I nearly went up to 88.

SGP:456 - 87 points. |

|

Caol Ila 4 yo 2019/2023 (61.4%, Milroy’s Soho Collection, 1st Fill Rivesaltes, casks #309863+ 309880)

Was this meant as a provocation, or was there sound reasoning behind offering a Caol Ila at just 4 years of age? And matured in Rivesaltes, no less? Let’s see… Colour: gold. Nose: no idea what kind of Rivesaltes this was, but it certainly shows. Feels a bit like a CI DE at cask strength, if you will. Mandarins, muesli, peaty smoke, rose petals, porridge, grape berries… With water: the distillate regains control, with a rather lovely combo of camphor, mint, and eucalyptus—quite unexpected in this context. Mouth (neat): very ‘trans’, with loads of peppered apples, apricot jam stirred with lapsang souchong, and blood orange. You get the idea. With water: same evolution as on the nose, once hydrated—more camphor, mint, eucalyptus and a touch of lemon. Finish: long, fresh, medicinal. Comments: there’s a provocative edge to this slightly transgenic CI, but the job’s been very well done. I was wary at first, but in the end, I like it quite a lot.

SGP:566 - 85 points. |

While we're at it with wine... |

|

Caol Ila, 10 yo 2015/2025 (58.3%, Lady of the Glen, refill ruby Port finish, 300 bottles)

The word ‘ruby’ is a bit unsettling, but ‘refill’ is somewhat reassuring. Beyond that, we trust Lady of the Glen. Colour: mirabelle with a faint onion-skin hue. Nose: not bad at all. Strawberry sponge, white chocolate and pistachio (not quite Dubai-style, mind), then chamomile and wild rose. It’s different. With water: damp earth, soot and seaweed return in earnest. Mouth (neat): a rather fine winesky, peppery and citrus-driven, with a good dose of bitterness. With water: more pickled now. Italian-style preserved lemons, if you like. In the end, it’s Italian cuisine that seems closest in spirit to malt whisky, which might explain its early success across the Alps. Finish: long, sweet-salty-bitter. Comments: for a ruby Port paired with peat—a rather improbable combination, let’s be honest—this one turned out rather well.

SGP:566 - 83 points. |

|

Caol Ila 17 yo 2001/2019 (57.9%, Gordon & MacPhail, Connoisseurs Choice, for Shinanoya Tokyo, refill American hogshead, batch #19/063, 247 bottles)

Colour: very pale white wine. Nose: oh lovely, almond milk, paraffin, fresh butter, fresh tar, shellfish and crustaceans, old fisherman's ropes washed up on the shore. Could one possibly get more classic—or more beautiful? With water: damp ashes, pencil lead and carbon paper. Mouth (neat): perfectly sharp and precise, with kippers, lemon, green apples and oysters. With water: even better—lively, taut, with coriander seeds and above all heaps of citrus and black pepper. Finish: razor-like, yet gentle. Then comes the green pepper. Comments: let’s not beat about the bush, this style sends all those finishings and wine cask maturations straight back to nursery school.

SGP:567 - 90 points. |

That was also the kind of bottle that proves Caol Ila is absolutely not a ‘lighter’ Islay. Right then, let’s carry on, randomly... |

|

Caol Ila 30 yo 1980/2011 (58.8%, Wilson & Morgan, Barrel Selection, bourbon, cask #4688, 196 bottles)

Colour: pale gold. Nose: candle wax and sweet almonds—here comes an old-style CI, brimming with charm and refinement. These are often the loveliest. Notes of smoked salmon, manzanilla, langoustines and linseed oil. With water: that old tweed jacket, the one that's weathered many storms, makes its grand return. Mouth (neat): absolutely stunning, though far edgier than the nose suggested—peppered lemon, Thai basil, and a near-brutal salty-citric blast that borders on the ‘chemical’—in the best possible way, mind, especially considering the number of Caol Ilas we cross paths with. Vive la différence, as they say in some parts of Paris. With water: a delightful touch of wonkiness now—smoked brine, resinous ashes, and plenty of mischief. Finish: medium in length, salty-bitter, just a touch challenging—but that’s precisely why we love it. Peppery seawater? Perhaps even a hint of strawberry. Comments: another cracking adventure. One or two bonus points awarded purely for the character.

SGP:366 - 90 points. |

Let’s finish with another “oldie” and there’ll be plenty more CIs tomorrow and in the days to come. The thing is, we’re hoping to reach 1,000 Caol Ilas before we shut down this wretched little website. You might say it’s doable — we were at 903 before this session… |

|

Caol Ila 12 yo 1982/1995 ‘Cask Strength’ (60%, The Cooper’s Choice, VA.MA Italy)

So many fine Islays from Vintage Malt Whisky Co.—Lagavulin, Port Ellen, and of course Caol Ila, which brings us here today. And let’s not miss the chance to taste some youthful old CI, as that’s often when the DNA shows most clearly. Colour: white wine. Nose: this is fairly massive, nothing light about it, yet an obvious elegance shines through—whitecurrants, top-tier sauvignon blanc, birchwood or beech, and paraffin oil. With water: doesn’t budge an inch. Perhaps a touch of virgin wool. Mouth (neat): superb tension, lemony and almost vinegary, with heaps of ashes and something like a grand vin jaune, à la Overnoy if that means anything to you. With water: the palate loses some structure with dilution, at least with our usual Vittel (Nestlé, are we still waiting on that cheque?) Finish: fairly long, salty and waxy, ending on green apple. Comments: magnificent, though not exactly easy drinking—water behaves very differently on nose and palate.

SGP:466 - 88 points. |

Right, ten at a time is more than enough. In any case, when we post longer sessions — like the 21 Karuizawas not long ago — it’s because we tasted them over multiple sittings. Right then, see you… |

| |

January 13, 2026 |

|

|

|

The Time Warp Sessions,

Indie Strathmill,

47 and 12 years old |

Ah, Strathmill! Another Speyside distillery that isn’t heavily marketed but which we love tasting, nonetheless. It remains relatively rare, and it’s probably not the modest official Flora & Fauna release that’s going to turn Strathmill into the next Macallan. At any rate, not just yet… That said, there have been quite a few fairly old Strathmills released by independent bottlers in recent years – but certainly not a 47-year-old like the one we’re about to start with today. This breaks with convention, not least because its bottling strength is fairly modest, especially compared to the little powerhouse we’ll be setting it against today.

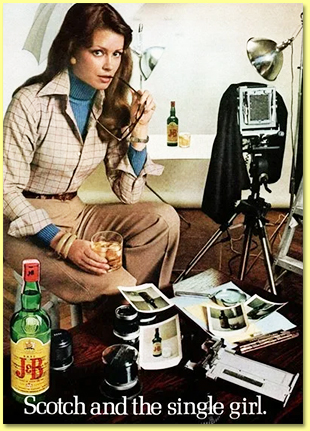

It’s worth noting that Strathmill, like Knockando, is one of the malts associated with the J&B brand. |

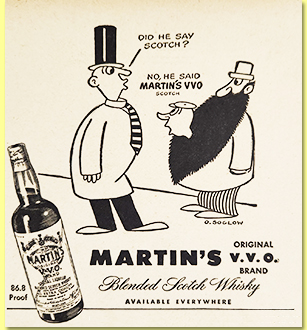

This famous press advert for J&B dates precisely from 1974, the year the first Strathmill we’re about to taste was distilled. |

|

Strathmill 47 yo 1974/2021 (41.5%, Gordon & MacPhail, The Dram Takers, Book of Kells, refill American hogshead, 50 bottles)

Who doesn’t like G&M’s famous Book of Kells labels? Hands up! In any case, here comes the oldest Strathmill we’ve ever had the pleasure of encountering. The previous holder of this enviable distinction was a 39-year-old 1962/2001 from a well-known Glasgow-based indy bottler. Sadly, that one had felt a little ‘over the hill’ on the palate (WF 83). Colour: gold. Nose: a curious medley of crushed banana and olive oil to start—are you in? Then a splash of orgeat syrup enlivened with a hint of mint and pine bud liqueur. Followed by whiffs of marzipan, waxed cardboard and beehive air. But worry not, there’s no sting in the tail; quite the opposite in fact, as it’s all rather elegant, with a restrained sort of refinement, gently lifted by the mint after a few minutes’ rest. Mouth: this is unmistakably an old whisky, with the wood having taken the upper hand, no doubt about it, yet there’s also lighter balsa and incense, green banana, more olive oil, and above all a rather striking and genuinely surprising salinity. A few wisps of tobacco too, along with a little bit of tea leaf for good measure. Finish: not very long, but the olive oil and salt do a fine job of keeping the whole thing together. One could almost dunk slices of crusty country bread in one’s glass and call it lunch. A bitter almond note lingers on the aftertaste. Comments: there’s something genuinely moving about this very old Strathmill, as if it were quietly bidding us farewell. With tremendous poise and a tear in its (our!) eye.

SGP:361 - 89 points. |

Quite possibly the complete opposite now… |

|

Strathmill 12 yo 1992/2005 (63.9%, Cadenhead, Authentic Collection, bourbon barrel, 216 bottles)

Colour: straw. Nose: it’s almost amusing, so intensely is it on cider apples, crushed slate and... not much else really, apart from a good dose of lawn. Nearly 64% vol., mind you... With water: about-face! Here come the greengages, angelica, fresh almonds, wee pears and fresh jujubes. Oh, and a touch of barley too... Mouth (neat): this one’s brutal, it goes full throttle on apple eau-de-vie, with even a glimmer of multi-column rum. Glug! With water: not a huge transformation, but the texture becomes oilier, slightly fattier, and now there’s a little lemon zest thrown into the melee. But what a beast! Finish: long, with more assorted lemons turning up, and a reprise—though in a more toned-down, sweetened manner—of that olive oil and salt combo last seen in the moving Dram Takers. Bit more bitterness on the aftertaste. Comments: well, it’s still a bit of a bruiser, let’s be honest.

SGP:371 - 84 points. |

(A thousand gracias, Tom) |

| |

January 12, 2026 |

|

|

|

WF's Quirky Little Duos,

today Hillside vs sparring partner |

You may have noticed that we've been sampling quite a few closed distilleries lately, and we're absolutely delighted about it, if only as humble archivists of Scottish styles and flavours. |

This time, it's Glenesk's turn, a distillery whose name was changed to Hillside around the mid-1960s, before reverting to Glenesk in 1980, only to be closed in 1985 and then almost completely demolished in the 1990s. So it’s indeed a Hillside, not a Glenesk, that we’ll be tasting today, as it was distilled in 1969. Led Zeppelin again, perhaps. After that, we’ll be looking for a little sparring partner from the same region, though there aren’t all that many to choose from. No, no Lochside currently in the stash.

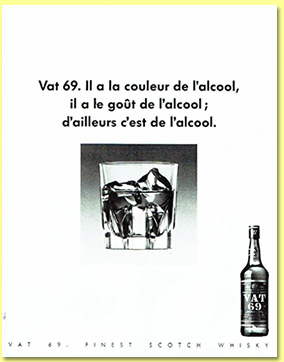

'Vat 69. It looks like alcohol, it tastes like alcohol; in fact, it is alcohol.' French press advert for Vat 69, whose base malt at the time was Glenesk/Hillside, 1980s.

For once, a brand that tells you nothing but the truth! |

|

|

Hillside (Glenesk) 25 yo 1969/1995 (61.9%, OB, Rare Malts)

We’ve only ever tasted around twenty Glenesk/Hillsides and would be hard pressed to summarise the style. But that said, another Rare Malt, the 1971/1997, had struck us as rather rough when we tried it, though that was twenty years ago (WF 82). Worth noting, Glenesk did exist as an official bottling back in the 1970s, under the William Sanderson & Son (DCL) banner. But we can't say it had left much of an impression on us in… 2004 (WF 60), we found it ‘weak and short’. Colour: pale white wine. Nose: straight off, it’s that grassy side again, green apple and paraffin, very typical of this series when you’re faced with examples drawn from what seems to be umpteenth-fill wood, as seems to be the case here. That’s good news, we like that—this way, you really connect with the distillate. Bit by bit, other rather shy fruits start peeking through, such as wee pears, quinces and medlars, then comes porridge, muesli and even soluble aspirin, you almost feel this baby was distilled yesterday. No OBE at all so far. With water: doesn’t move an inch, it just becomes more expressive on the nose, and as a result quite splendid. Very impressive, not unlike some old Rosebanks. Mouth (neat): immense arrival, hyper-lemony, yet wrapped in a chalky and faintly honeyed coat. It sends a lovely shiver down your spine, especially at this strength, but we’re into that sort of thing, aren’t we. With water: splendidly lemony, extremely zesty, very mineral too, then gradually unfolding on small orchard fruits, with utterly mad elegance. Finish: very long and hardly changes. Slightly sharp, superb, with a surprising note of blueberry popping up right at the end. Comments: the best Hillside/Glenesk we've ever come across, though you'll tell me that wasn’t difficult. I believe this is one worth actively tracking down; the bottle we’re tasting is No. 5021, so it must’ve come from a fairly large batch.

SGP:561 – 91 points. |

As we don’t have another Glenesk to hand, we’ll quickly look for another malt from the area nearby Montrose. A Glencadam, for instance, as the distillery is less than half an hour away... But we’ll keep this brief, as the comparison doesn’t make a huge amount of sense, we agree. |

|

Glencadam 13 yo 2012/2025 (53%, Decadent Drinks, Decadent Drams, refill barrel, 282 bottles)

Judging by the label, this ought to be a rather diabolical whisky. Colour: pale white wine. Nose: this is mad, believe it or not, but it’s remarkably close to older malts such as, say the tougher North Port (we've tried some a few weeks back), with cider, soft ale, bruised apples, quince, biscuit dough, sourdough… Truly, it’s mad. With water: an old bouquet of flowers, paraffin wax… Mouth (neat): this time it’s livelier, more herbaceous, more bitter too… It’s quite a full-bodied malt, but not terribly, um, ‘sexy’. With water: the pears take charge and never let go. Bonkers. Finish: fairly long, wildly rustic at its peak, I’d say you’d need to be a young Scot from the wilder reaches to genuinely appreciate this kind of rather uncivilised malt. Comments: right, we understand, don’t we. It sure gets the job done, but the old Hillside would rather soundly trounce it all the same.

SGP: 451 - 84 points. |

| |

January 11, 2026 |

|

|

A few rums to get through the snow and storms

Winds reaching 200 km/h along the Atlantic coast, thirty centimetres of snow here and there, that’s more than enough to have us dreaming of the tropics and their most famous produce: mangoes. I mean, rum. Let’s see what we can find to warm us up (though I should remind you — as any skier knows — that technically, alcohol doesn’t warm you up, quite the opposite). Let’s begin with our traditional little apéritif… |

|

Mount Gay ‘XO Triple Cask Blend’ (43%, OB, Barbados, +/-2025)

Unclear proportions of column and pot still rum in the mix, sadly undisclosed, matured in American whisky casks—presumably American oak, though perhaps not first fill—and in Cognac casks, so French oak, but again likely not first fill either. Still with me? Colour: full gold. Nose: honestly, rather lovely to start with, opening on a touch of nail varnish before moving towards roasted peanuts and vanilla cream, eventually settling on shortbread biscuits dipped in milk chocolate. The whole affair feels fairly composed, not too loud, which we do quite appreciate. Mouth: follows on nicely from the nose, with good weight despite the modest strength, showing a bit of mango juice (there it is)) and fig cake. Hints of liquorice, very faint, though no obvious raisins from the Cognac casks, which might have been expected. Finish: not overly long but very well balanced, with notes of black tea. Comments: very likeable, fairly dry, and I do find it a touch better than the earlier XO (WF 82).

SGP:351 - 83 points. |

|

Foursquare 13 yo 2007/2021 (62.1%, The Colours of Rum, Barbados, No.10, cask #14, 328 bottles)

This one, too, could be considered a kind of finishing, as the wee thing spent eleven years in the tropics before a final two in a former English malt cask, likely St. George. Yes, we’re running a tad late here... Colour: full gold. Nose: very close indeed to Mount Gay—could one speak of a unified Barbadian style? Fairly light structure but with serious alcoholic clout, showing vanilla, nail varnish, macarons, and white chocolate... With water: still weightier and more unctuous than its compatriot, which might, I do say might, point to a greater share of pot still. Mouth (neat): hefty power, a sharp and energetic arrival that has one wondering whether that English malt wasn’t kind of peated. Quite a bit of lime, verging on premixed mojito, indeed we're being dramatic again. With water: everything softens and rounds off nicely, though the welcome liveliness remains. That impression of light peat has now vanished. Walnuts, pecans, café latte. Finish: a touch of drying oak, though still entirely pleasant. Remarkably close to Mount Gay in style. Comments: handsome bottle, as expected.

SGP:451 - 85 points. |

|

Spanish Heavy Rum 18 yo ‘Long Fermentation’ (59.2%, C. Dully Selection, 214 bottles, 2025)

This one fermented for no fewer than three weeks in wood, was pot-distilled, and matured in Spanish oak from the Pyrenees. In theory, proper Spanish rum (as opposed to Spanish-style or foreign rum dressed up in Spanish packaging) ought to hail from the Canaries, perhaps Arehucas? Then again, we really haven’t the faintest clue... Colour: gold. Nose: smells of cane juice, old copper, roasted pecans and black turrón... With water: more nougat, hazelnut cake, and assorted Lindt chocolates (as the house of C. Dully is Swiss, after all) ... Mouth (neat): phew, not a trace of the sugar that’s usually dosed with wild abandon in rums of this persuasion. We do get that faint metallic touch we rather enjoy, alongside ripe passion fruit and toasted oily nuts. So far, not exactly ‘heavy’ on the palate, but a few drops of water could shift things. With water: indeed, not a total volte-face but we’re now finding notes of brine, salmiak, earth, even olives, which do rather evoke those rums from Madeira. But Madeira is in Portugal, not Spain (bravo, S.) Finish: long, salty, brisk, now bringing in salted anchovies. Comments: astonishing how much water transforms this one. Our rating refers to the hydrated version. In any case, I believe this is the finest Spanish rum we’ve ever tasted.

SGP:552 - 85 points. |

|

Cuban 46 yo 1978/2025 (57.5%, The Whisky Blues, ex-Islay STR barrels, cask #2315303, 268 bottles)

So it turns out they’ve been STR-ising whisky casks too, not just wine casks, though one suspects this might simply be automated rejuvenation à la Cambus Cooperage. On paper, it sounds a touch Frankensteinian, but as always, the truth lies in the glass… Colour: deep gold. Nose: at first nosing, this leans towards a low-mark Jamaican, with a modest ester count and lashings of roasted and salted peanuts. Clearly richer than your average elderly Cuban. With water: cigar ash and Tesla brake pads. Mouth (neat): quite the surprise—this is peated rum, no less. Ashy coffee. It’s like a whole new sub-category, though we've encountered a few like it before—just not a 46-year-old Cuban, mind you. With water: well, it works, though it clearly straddles two worlds. Finish: medium in length, more rooty now, which often happens with these. Comments: something of a Cuban in Jamaican drag, rather like those old Porsche Turbo-looks. No turbo, but jolly good fun.

SGP:453 - 85 points. |

|

Navy Blend (57.1%, Famille Ricci and RumX, blend, 2025)

A British Navy-style blend uniting Caroni, TDL, New Yarmouth, Hampden and Diamond—a true feat for a French house, I must say, in channelling the spirit of the Royal Navy. Then again, it’s been over two centuries since old Napoleon’s time. The youngest rum in the mix is a 2014 Hampden, so we’re looking at something around 10 or 11 years old here. Psst, could we one day have a rhum of the Marine Nationale as well? Colour: amber. Nose: a proper big band of a rum, no doubt about it, with perhaps only the TDL manning the violins—then again, heavy TDL certainly exists. I do love this sort of ultra-classic composition, though it leans heavier than, say, Black Tot. With water: it softens, clears up, grows more refined, but also heads towards petrol and olive oil territory. That, we do enjoy. Mouth (neat): it’s heavy, though far from overwhelming, lifted by some rather lovely preserved citrus fruits. With water: this is where it truly shines for our palate, the saline edge swelling beautifully, almost evoking black olives. Finish: long, pure salmiak liqueur, if such a thing exists, with a touch of slightly burnt caramel in the aftertaste. Comments: really excellent for a blend.

SGP:562 - 86 points. |

Check the index of all rums we've tasted Check the index of all rums we've tasted

|

| |

January 9, 2026 |

|

|

|

The Time Warp Sessions,

today 1989 Cragganmore twenty years apart |

If there’s one distillery we don’t taste often enough for my liking, it’s Cragganmore. Its various expressions—apart from perhaps a few ‘secret’ editions—are as rare as a dictator’s remorse. At least we can count on some older bottlings we’ve yet to sample to keep flying the flag high... |

|

Cragganmore-Glenlivet 16 yo 1989/2005 (58.6%, Cadenhead, Authentic Collection, butt, 678 bottles)

The few 1989s by Cadenhead (two, in fact) that we’ve already tasted were very much to our liking. Perhaps owing to the flat and broad stills and, of course, the worm tubs. Colour: full gold. Nose: fat and extraordinarily winey. And by winey, I mean it exhales notes of venerable white wine of great pedigree, perhaps a Montrachet or one of its closely related crus. What follows is a curious mix of rose petal and camphor with just a touch of paraffin. In short, a highly unusual nose… With water: the paraffin remains and is joined by linseed oil and charcoal fixative. In short, a malt for artists. Mouth (neat): incredible, there's little difference with the nose, so we’re still on old Chardonnay and paraffin, but also an immense bitterness that would send both Fernet-Branca and Jeppson’s Malört back to the Graduate School of Bitterness. With water: barely budges and remains extremely bitter. But we do like our bitterness firm, even if we may well be the only ones in the entire village. I mean, to this extent. Finish: very long, very bitter, and even rather salty. Was this a fino butt? Comments: a proper warrior, this Cragganmore, one that doesn’t compromise in the slightest.

SGP:172 - 87 points. |

And now, with twenty more years of maturation… |

|

Cragganmore 36 yo 1989/2025 (51.8%, Whiskyland, Decadent Drinks, refill hogshead, 158 bottles)

This baby will no doubt be less bitter than its sparring partner of the day. Colour: gold. Nose: we do find some elements of the younger one, notably that paraffin and liquid wax profile, but here it’s taken on a near-fractal tertiary development, veering towards flowers, apples and greengages, rounded out with walnut oil, peanut oil and sesame. It’s absolutely lovely. With water: freshly cut hay in the middle of August. Mouth (neat): utterly splendid, beautifully old-school, with those same bitters again but now softened and more delicate, along with heaps of citrus zest, some rather serious green tea, and the sensation of biting into a beeswax candle. What’s most spectacular is the overall balance. With water: and the hay returns. Our neighbours in the Vosges make hay wine and I must say, it can be really good, especially when said hay contained a good number of various flowers. Finish: long, narrowing onto the bitters and waxes, which is perfectly normal. Overripe apple peeks through on the aftertaste. Comments: the best Cragganmore of the year so far (that’s clever, S.) You can tell it’s an old malt whisky, yet it has none of the usual drawbacks—no dryness, no overt tannins, no cardboardy bits… in short, none of that here, which is rather surprising. A slight cerebral touch all the same. I adore it.

SGP:461 - 91 points. |

| |

January 8, 2026 |

|

|

|

|

Little Duos,

today indie Glen Ord |

I feel Glen Ord is a distillery unfairly overlooked by enthusiasts. It is one of the greatest malts in the world, and that’s without even mentioning the adjoining maltings and their impact on the flavour profiles of many a modern whisky. |

|

Glen Ord 11 yo 2012/2024 ‘100 proof Edition 22’ (57.1%, Signatory Vintage, 1st fill bourbon barrel)

Colour: white wine. Nose: Ord, that’s apples and wax in near-perfect proportions, almost Da Vinci-esque, and you do feel it here, with utter austerity, a touch of chalk, and a kind of intellectual honesty that reminds us that indeed, distilleries are human too(what?). With water: freshly cut grass, fruit peelings, green pepper and crêpe batter. Mouth (neat): total perfection, though in a very simple and rustic mode. In short, there’s green apple galore and not much else for now. The simplest expression of a flawless malt whisky. With water: same again, with just a drop of barley syrup. Finish: long, grassy, herbaceous, fatty, with cactus. Comments: this is completely love and hate. I really don’t know what to add. In truth it’s Freudian, not easy, and on the palate it leads us to question ourselves. So be it.

SGP:361 - 83 points. |

|

Glen Ord 16 yo 2008/2024 (53.7%, Artful Dodger, bourbon hogshead, cask #305072, 295 bottles)

Colour: pale white wine. Nose: this is very close in style, showcasing the glories of refill wood, it’s austere, grassy, with cider apples, barley sugar, candied sugar, even a little limoncello. With water: bread dough, flour, fern... Mouth (neat): excellent, taut on herbs and leafy things, with tart apples and lime. This sharp edge is rather spectacular. With water: more body, apple compote, porridge. Finish: same, long, austere, vegetal, though smoothed out by a dash of barley syrup. Hints of Williams pear in the aftertaste. Comments: Mother Nature in your glass, without the slightest artifice.

SGP:451 - 85 points. |

| |

January 7, 2026 |

|

|

A Speyburn trio

Another distillery we’re very fond of, even if it’s not (yet) totally a blue chip. Here too, we make a point of featuring it regularly on WF. Right, let’s start by getting the inevitable Bordeaux finish out of the way, isn't it in malt whisky the modern-day equivalent of the drum machine in 1980s pop rock?… |

|

Speyburn ‘Bordeaux Red Wine Cask’ (40%, OB, Traveller Exclusive, 2025)

Colour: gold. Nose: tomato vine and raspberry yoghurt, plus a bit of new rubber and some M&S chocolate cream. Not terribly pleasant, between us. Mouth: blackcurrant buds, pepper and candied cherries. That faint rubberiness lingers. Finish: not that short, fairly bitter, very much on ultra-young cabernet, green pepper, black pepper, stems and leaves. Comments: it’s likeable and drinkable, but honestly rather tricky. Still, what an idea! Granted, every distillery in Scotland has either done this or flirted with it, but even so… Well, it’s still better than the fairly infamous early 2000s Bowmore Claret, I’ll give you that, and not far off the slightly pitiful Glenmo Margaux Cask Finish from around the same period. The good news is it can only get better from here.

SGP:371 - 65 points. |

|

Speyburn 10 yo 2014/2025 ‘Super-Dupper Lemony’ (50%, Elevenses, refill bourbon hogshead, 361 bottles)

We do like the packaging in this range, a welcome change from crystal decanters and mahogany coffrets. Colour: pale white wine. Nose: pear spirit, apple eau-de-vie, vanilla cream and a family-sized bag of Haribo pick’n’mix. Not forgetting the liquorice allsorts... You couldn’t get much younger and fruitier than this. With water: no real change, nor was any needed. Mouth (neat): very much on young barley eau-de-vie, and we do enjoy that kind of thing, even if it’s simple and mainly fruity, especially on lemon and orange sweets. With water: the water adds a bit of complexity, saline touches, lemon grog, even a hint of miso. Finish: fairly long, close to the barley, with some bitter herbs. Comments: one might be tempted not to add water to this wee natural baby, but that would be a mistake.

SGP:551 - 84 points. |

|

Speyburn 18 yo (46.5%, Living Souls, first fill bourbon barrel, 2025)

Colour: white wine. Nose: surprising wafts of model glue to start with, neoprene, then fresh kirsch and almond milk, followed by green bananas. Very nice evolution in the glass, rather captivating if you give it a minute or two. Give it five, and it ends up as a charming fruit salad. Mouth: interesting palate from a cask that wasn’t overly active, though clearly given plenty of time, allowing a whole array of smaller descriptors to emerge—tiny berries (rowan, elder, service tree, holly eaux-de-vie) and little cider apples. The whole is wrapped in a touch of honey and barley syrup. Finish: long, lovely, more lemony, greener, with curious notes of edible flowers—pansies, borage… Bitterness builds in the aftertaste. Comments: seems rather rustic at first but if you let it unfold, it repays you well, only the slightly bitter aftertaste is a touch more challenging.

SGP:551 - 85 points. |

| |

January 6, 2026 |

|

|

|

|

Little Duos,

two official Jura |

Jura is another distillery we absolutely don’t want to give up on. Even if the current releases aren’t exactly mind-blowing — especially with some of those odd casks — there have been some that were pure magic. If you don’t believe me, have a look at this old session from November 2012: . Right, we can assume the next two drams won’t quite be of the same calibre… |

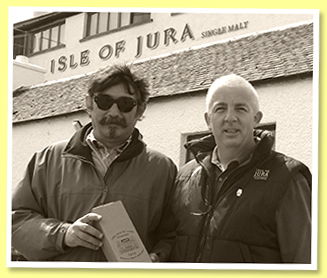

The author at Jura with the manager at the time,

Mickey Heads, a long time ago, before he crossed

the Sound of Islay to take over at Ardbeg. |

|

Jura 14 yo (40%, OB, American Rye Cask, 2025)

We’re not quite sure what the point of such a finish might be, other than rye being somewhat fashionable these days. Let’s see… Colour: gold. Nose: it’s simple, not very bready, not very rye-forward, but balanced, gentle, with acacia honey and shortbread. No complaints at this stage. Mouth: light, slightly marked by oak, black tea, then a hint of wholegrain mustard, possibly rye-related. A few wisps of tobacco that seem to have escaped from an unfiltered cigarette (as far as I can remember). The strength holds up well enough for something bottled at minimum ABV. Finish: not very long, but with faint touches of lemon and salt, plus a dash of cinnamon. Comments: frankly, this is well done.

SGP:451 - 80 points. |

|

Jura 16 yo (43%, OB, bourbon barrel, travel retail, 2025)

We had found the recent 16 yo ‘Perspective No.01’ really very good, though that one was bottled at 46.5% (WF 86). Here we’re more in travel retail territory, the kind aimed at the idle traveller. Colour: full gold. Nose: very honeyed, very much on orange cake, then sultanas and apricot jam, before a little wax and even polish show up, along with faint touches of wood smoke. All very very pretty, it must be said. Mouth: not that far off the 14-year-old, really, just a little punchier, with that same slight mustardy note reminiscent of Fettercairn, followed by hints of beer bitterness and even lemongrass. It’s really lovely in fact, with a fair bit of character. Finish: fairly long, slightly oily, with black tea and green pepper, all backed by lemon. Comments: we dare not imagine what this might have been like at 46% vol. Or rather yes, we dare…

SGP:552 - 86 points. |

Check the index of all Jura we've tasted Check the index of all Jura we've tasted

|

A PDF for posterity – and for the number crunchers

One last thing before we officially close the book on last year: we’ve put together a quick and dirty ranking of the number of tastings logged on WF from the very beginning up to 31 December 2025, broken down by distillery – starting with Caol Ila and its 903 tasting notes to date. By the way, we expect to hit the 1,000 Caol Ila mark by the end of this year or the beginning of next. Expect forty new ones very, very soon.

In total, that makes 28,615 tasting notes.

Whiskyfun-Tastings-2002-2025.pdf |

| |

January 5, 2026 |

|

|

|

|

WF's Little Duos,

two rare vintage Port Ellens of very high strength |

|

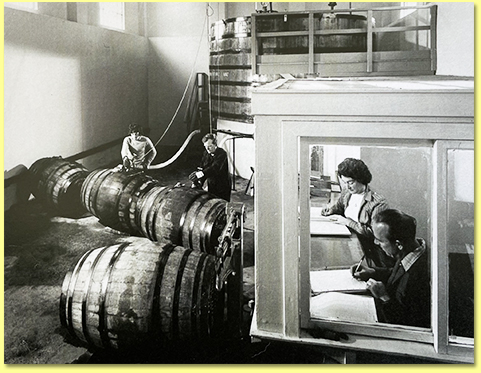

| Cask filling at Port Ellen, mid-1970s (Diageo) |

I was just thinking the other day that we didn’t even taste any Port Ellen over the holidays — which is really quite unusual. Especially considering that one of them, the official 42-year-old released for the 200th Anniversary, was our favourite new whisky of last year. To make up for it, we’re going to select two older, yet still relatively young versions — rather rare ones, and above all, from vintages that are quite uncommon. |

|

Port Ellen 17 yo 1980/1997 (61.8%, Cadenhead, Authentic Collection)

We know full well that the very pale whiskies from this ‘small cream label’ series were often perilously close to kerosene, albeit a kerosene of immense charm, letting the distillate take centre stage while pushing any notion of oak neatly aside, which rather contrasts with what most contemporary Scottish brands tend to do these days, does it not. Anyway, let us buckle up… Colour: pale white wine. Nose: frankly, it really does smell like kerosene, or like the tarmac at a provincial airport in the middle of the summer holidays. But the fact remains that, gradually, everything becomes both oilier and softer, with almond milk, damp cardboard, hair lacquer, a few touches of tar and cabbage forming quite the duo, plus just a few drops of lime juice. Yet all of it remains impressively austere for the time being. With water: hardly changes, save for a hint of Woolite and the floor of an old petrol station. Mouth (neat): an explosion of salt and tarry cardboard, quite incredible. Even the saltiest Taliskers are not as salty as this. Quick, some water… With water: still vast quantities of salt. We're not talking ‘salinity’ or ‘minerality’ here, but rather proper sodium chloride, even potassium salt. Mad stuff. Finish: virtually eternal, and still massively salty. Comments: people often talk about seawater, but this one really does make you feel as though you're drinking it. Extremely hard to score—there’s something downright philosophical about this incredible malt.

SGP:267 - 89 points. |

|

Port Ellen 15 yo 1977 (63.6%, Sestante, +/-1992)

One rather fears the worst given the bottling strength. Just kidding a little, though not too much… Some of the 1977s from similar sources were notoriously tricky to handle, even bordering on unpleasant. Colour: gold. Nose: no, not at all, it’s almost as gentle as a lamb compared to Cadenhead’s salt bomb, despite the lofty strength, with those splendid notes of bitter almond and earthy tar that scream ‘PE’, and above all, that gentian mingled with liquorice. With water: magnificent, very precise, very PE, very ‘Rare Malts’, with more brine, tar, coal ash and gherkins. Mouth (neat): it’s beautiful, very clean, very peppery, quite a bit on hydrocarbons and even salt, but once again, it comes across almost polite after the 1980 of doom. With water: the cavalry is unleashed—samphires, oysters, petrol, seaweed, olives, salmiak, lime, and still loads of tar. Truth be told, Port Ellen without tar would be Glenkinchie (utter nonsense, S). Finish: long, lively, saltier once more, yet magnificently rooty too, with the gentian and black olives charging back in. The peppers fire back in the aftertaste. Comments: it’s obviously superb, a proper beast of a dram.

SGP:367 - 92 points. |

| |

January 4, 2026 |

|

|

|

The Rum Sessions,

The rums are back on the table as 2026 begins |

It’s true that cognacs and armagnacs stole the show at the very end of last year, so it’s time to return to the finest expression of sugarcane — starting with a suitable aperitif… We’d love to go with the new Hampden 15-year-old, which we do have on the table, but it might just overshadow the rest of our tasting session, so we’ll save it for later in the lineup. So then, an aperitif… |

|

Havana Club ‘Iconica Seleccion de Maestros’ (45%, OB, Cuba, triple barrel aged, +/-2025)

A seemingly boosted version of the famous Seleccion de Maestros, of which we had greatly enjoyed an earlier edition bottled at 45% vol., back in 2013 (WF 85). But I’m not quite sure what sets this ‘Iconica’ version apart from the others, it still comes at a very modest price. Colour: full gold. Nose: a very Cuban style, as also seen at Santiago’s, built on toffee and roasted peanuts lightly scented with aniseed. A few glimmers of copper (old coins) then a mix of toasted wood and liquorice which suits it rather well. It’s really more vivid than your typical Havana Club bottlings, in my humble view. Mouth: the palate mirrors the nose, though it’s a little sweeter and more coated, the one part that’s a tad off-putting to me. This moderate sweetness persists throughout, with notes of liquorice, orange zest, dark nougat, English chocolate... Finish: fairly long though the candied sugar ends up taking the lead. Comments: a bit of a shame, it was shaping up very, very nicely but that liqueur-like aspect on the palate feels a little too much for me.

SGP:740 - 79 points. |

Seeing as we’re going sweet… |

|

Dos Maderas ‘Atlantic’ (37.5%, Williams & Humbert, blend, +/-2025)

A blend of very young Guyanese and Barbadian rums, finished in PX sherry casks in Jerez. Several Dos Maderas expressions had struck us as far too sweet in the past. That’s perhaps why we hadn’t gone near them for the past twelve years. I’ll also point out that the bottling strength of 37.5%, the legal minimum, is always a little frightening. Colour: deep gold. Nose: very light, on cane syrup, roasted nuts and hand-rolling blond tobacco. A very prominent ‘high-column’ profile. Mouth: light and far too sweet for me. I believe this sort of baby is meant to be enjoyed over ice, and do remember that lowering the temperature also dials down the sweetness. As they say, it’s designed for that. Finish: short, very light. Molasses, caramel and two raisins. Comments: clearly not a ‘sipping rum’, as they say in the reference books.

SGP:620 - 50 points. |

As we're into blends now… |

|

Rh05 (65.4%, Zero Nine Spirits, Cyberpunk series, Jamaica and Belize, 200 bottles, +/-2024)

We hadn’t yet summoned the courage to taste this blend of 60% Jamaican and 40% Belizean, due to the rather unusual combination of an unaged-sounding blend notion and a near-lethal bottling strength. I ask you, where does one even place this in a lineup? Colour: full gold. Nose: would you be surprised if I said the Jamaican part seems to dominate? A very curious mix of loads of ethanol, tar with menthol and aniseed, then a touch of burnt pecan pie. But let’s quickly add some water… With water: fresh cane juice suddenly rises to the top, with a surprising balance. I’d guess this came from a ‘light’ marque Jamaican, more low-ester. Mouth (neat): very strong, drying, packed with ashes, tar and some extreme salmiak. Let’s not push our luck further… With water: more esters on the palate than on the nose, still that tarry liquorice side, then a lovely pepper and lemon combo. Finish: long, fairly fresh, more earthy, with a few drops of rougail sauce. The Jamaican keeps the upper hand. Comments: not the easiest ride, and every drop of water you add shifts the balance of the blend. But it’s huge fun and very good indeed – oh yes, this baby makes you work.

SGP:553 - 86 points. |

|

Fiji Islands 15 yo 2009/2025 (55.1%, Planteray for The Whisky Exchange, Kilchoman cask)

Well, one can hardly complain about the crazy ‘cask bill’ here (9 years bourbon + 2 years Ferrand cognac + 4 years Kilchoman), since we’ve often noticed connections between certain Jamaicans and some Islays, and Fiji—presumably South Pacific—is no doubt the most Jamaican of the Pacific rums. Right, are you still with me? Colour: gold. Nose: now this is something else. A cucumber salad with olive oil and pink pepper, salted and smoked anchovies, a Bellini (champagne and peach purée), then a few old papers and discarded cardboard boxes on… Islay. In any case, it’s all of a piece, not some incongruous mash-up of conflicting profiles. With water: a lovely blend of varnish, paint, sea water and smoked oysters. Mouth (neat): let’s say it—the Islay takes control and never lets go. It’s packed with ashes and smoky things. As for the tarry notes, impossible to tell whether they hail from Fiji or from Scotland. With water: more rooty. Powdered ginseng. Finish: long, with ashes returning in force, along with olives. Comments: twenty years ago they’d have called this an ‘experimental spirit’. I think it’s a rather lovely cross-category blend, and it does make sense, if you overlook the 19,000km between Fiji and Islay (by boat). Ah, and if only we had the time, we’d be enjoying a Kilchoman Rum Cask right now, for comparison. Alas, we don’t have the HSE Kilchoman finish to hand.

SGP:366 - 86 points. |

|

Haiti 50 yo 2004/2024 (58.6%, Malt, Grain & Cane for 20th anniversary Bar Lamp Ginza, 159 bottles)

Lovely dragon-serpent on the label – we’re in Singapore. This secret Haitian could be a clairin, though I very much doubt it, it’s probably Barbancourt, though what style exactly is anyone’s guess, as that famous house has changed considerably over the decades. At its core, it’s cane juice, though distilled in tall columns rather than the Creole stills used in Martinique or Guadeloupe (for the agricoles). Colour: gold. Nose: fresh and light cane, rather aromatic, which might bring some Cubans to mind, with plenty of vanilla and candied orange. With water: lighter still, with loads of finesse. Light honeyed notes. Mouth (neat): again that very light profile, reminiscent of some Scottish grains, yet there’s still texture and above all a good deal of elegance, around citrus and caramelised cane. With water: some small spices arrive, aniseed, paprika, pink pepper. The aftertaste is very gentle. Finish: not that short actually, fresh, on candied citrus and cane, then some heather honey. Comments: it’s rare to find such a light rum from an indie bottler – bravo! Above all, it has remained natural, while so many brands tend to boost this kind of rum with assorted additives for texture and flavour.

SGP:530 - 85 points. |

|

SVN 2003/2025 (61.3%, Vagabond Spirit, Silva Collection, La Réunion, 240 bottles)

SVN is rather like HMPDN, you can more or less guess what it is. In this case, the ageing took place mostly on the island, followed by a few years on the continent. Amusingly, when rum folks speak of ‘continental ageing’, they often count the United Kingdom as part of said continent. Someone should ask Mr Farage. Colour: amber. Nose: superb, on incense, mint, varnish, pink bananas, toasted macadamia nuts and hairspray. Hints of cedarwood and humidor, though no cigars at this point. Doesn’t really smell like a ‘Grand Arôme’. With water: oh that’s lovely, some top-notch soy sauce and even notes of Marmite, in any case plenty of glutamate. Controversial as an additive, but we do like it in our spirits. It’s rather like gunpowder in a way. Mouth (neat): rich, ample, fairly bourbony, peppery, slightly astringent at this stage but in the prettiest of ways. With water: water does it a world of good. Pineapple jam, resinous woods, dark chocolate, oysters, liquorice… Finish: very long, saltier still, with generous amounts of liquorice and a touch of ash and Chartreuse. We are talking green Chartreuse indeed here. Juniper in the aftertaste. Comments: what complexity, what an adventure!

SGP:562 - 90 points. |

We were just talking about it… |

|

Hampden 15 yo (50%, OB, Jamaica, 2025)

Pure pot still of course, fully aged on site, with 75% angel’s share. We won’t go insulting the angels now, will we—you never know... Worth noting, on-site ageing only really began in 2010, so fifteen years ago. It’s still something rather new, not quite as traditional as one might like to believe. Right then, shall we? Colour: amber. Nose: there’s less zestiness and tension than in continentally aged versions, but more breadth and, above all, more jams made from exotic fruits, tamarind, banana, guava, always with a faintly fermentary edge. Lovely cedarwood above it all. With water: and here come the varnishes, tars, paints and carbon. Mouth (neat): superb, on mint dark chocolate, mango and salt. The influence of the cask is much more pronounced than in most indie versions, but it works beautifully. Dark tobacco, a faint ‘pliers-on-the-tongue’ effect. We’re masochists anyway. With water: once again the primary elements stage a coup, on pepper, glue and salted tar. Finish: returns to something more rounded, chocolate, coffee, orange cream, then a fino-like note in the after-finish. Comments: well, we love it, and this new 15 is going straight on the same shelf as Springbank 10, Talisker 10 and Ardbeg 10. There, job done. No ten no deal, fifteen I’m keen.

SGP:562 - 91 points. |

Go on, shall we treat ourselves to a bit more Hampden? It is the new year, after all… |

|

HD 1997/2025 ‘C<>H’ (59.6%, The Whisky Jury, The Many Faces of Rum, Jamaica, refill barrel, cask #1, 195 bottles)

I suppose the label is meant to suggest this is an unicorn of a rum. This marque clocks in at 1,300 to 1,400 grams of esters per HLPA. That’s a lot. Colour: full gold. Nose: more ‘aggressive’, in the best sense, a sort of mix between UHU and Pattex glues, with litres of spicy olive brine and a good three litres of two-stroke fuel mix—you know, for the lawnmower… With water: plastic model glue and a big parcel from Temu, phthalates, PFAS and formaldehyde included. Sounds frightening, but I adore these aromas, no doubt tied to childhood, as often. Mouth (neat): you already know it’s going to be on par with the official 15, despite a rather different style—sharper, almost more violent, saltier, more ‘chemical’ (whatever that means—of course it’s just organic chemistry), almost vinegary. With water: softer and saltier, closer to olives and brined lupins. Finish: very long, very saline. Comments: all these petroly notes might be off-putting, but I find them utterly magnificent. Is it serious, doctor?

SGP:563 - 91 points. |

Right, let’s finish with a rum that’s likely lethal. We tried calling our lawyer again, but once more, he was out playing golf. As long as he’s not at Mar-a-Lago or Turnberry — absolute sanctuaries of good taste and elegance, right — I’d say it’s fine, nothing that warrants an immediate dismissal, guns blazing… |

|

Hampden 2023/2025 ‘HLCF’ (83.4%, The Colours of Rum, Pure Rum, 60 bottles)

HLCF means 500 to 700 grams of esters. The label ‘pure rum’ coupled with a bottling strength of 83.4% ABV feels even funnier than a classic Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis piece. There sure is little water. Colour: very, very pale white wine. Nose: almost nothing, I mean ethanol, kerosene and apple juice. Really, apple juice. With water: damp earth and glue emerge around the 45% mark, at which point the (relatively) moderate ester count lets the fruits speak. Apples, pears… Mouth (neat): right, let’s dare... Zut alors, it’s excellent! Can it be at this strength? Of course, as long as you avoid sipping this near open flames, or any electronics ordered from that earlier-mentioned source (Temu, ha). Otherwise, this mix of lime, Williams pear, fuel and seawater is rather glorious. In small sips, obviously... With water: perfect, salty, petroly, acidic, lemony, maritime. No prisoners, even at 45%. Finish: very long, more medicinal, though it’s not quite old-school Laphroaig either. Bright lemon, salt, pepper, ideas of camphor. Comments: that’s the thing, everyone talks about maturation, the influence of location and so on, but for a distillate like Hampden, which is already perfect after just a few months, all that sounds a bit superfluous.

SGP:553 - 90 points. |

Hold on, looks like we can squeeze in one final drop… |

|

Jamaica 5 yo 2018/2024 ‘LROK’ (67.5%, Flensburg Rum Company for Kirsch Import and Sea Shepherd, first fill oloroso hogshead, 311 bottles)

LROK is a fairly light ester marque for Hampden, though one always remembers nothing’s linear in this game. Right then, to the health of Paul Watson, honorary citizen of the City of Paris and holder of a French residency permit since November 2025. For once we’ve done something sensible in this bloody country… Colour: full gold. Nose: the impact of the oloroso seems marginal, there, that’s said. The rest unfolds over new Ikea wood (thank goodness not the meatballs), olive oil, seawater, neoprene glue and carbolineum. With water: green walnut! That’ll be the oloroso… And menthol tobacco. Mouth (neat): magnificent, balanced, saline and rich on lemon coffee cream. Though mind you, these very high strengths can hit hard… With water: perfect, everything nicely poised, like a premium car just back from servicing. Lemon, ashes, tar, seawater, olives, chervil, praline. Finish: perhaps a little less biting than expected, but joyfully salty. Comments: perhaps not the grandest Hampden ever bottled in the end, but it’s still extremely good. Cheers Sea Shepherd and Paul Watson!

SGP:452 - 88 points. |

Check the index of all rums we've tasted Check the index of all rums we've tasted

|

| |

January 3, 2026 |

|

|

|

Angus's Corner

From our correspondent and skilled taster Angus MacRaild in Scotland

Illustrations, Darius Pronowski

Whisky and terroir:

Part Three and last |

|

|

|

Terroir is a useful way to think about whisky because it acts as a challenge to the official industry consensus about itself, about its product and about its history. Scotch Whisky is commercially dominated by blends, but it is underpinned by malt whiskies. We are told time and time again that if it wasn’t for blends there would be no malts etc. But is that true? Is there any reason, if the 1909 Royal Commission had gone the other way and found in favour of the Distillers, that a different kind of industry, one perhaps more like what happened with French wine, might have evolved? It’s impossible to know, but I believe that the secondary industry that is emerging today, largely consisting of smaller, independent distilleries intent on doing something different to the mainstream industry, is perhaps, finally, an indication of what has always been possible with Scottish malt whisky. Not everyone in this emergent wave of distilleries adheres to a philosophy of terroir, but almost everyone borrows some of its adjacent ideas and language – everyone wants to talk about, and demonstrate, local, sustainable, quality, individuality etc. |

|

|

|

|

|

In the same sense, it is useful to really think about it technically. The argument against terroir existing in whisky is often underpinned by a focus on distillation, on its violence and the hot, turbulent nature of the process. But these arguments often frame distillation as a process of deletion, when it is really one of concentration. Is the collective weight of ingredient and site-specific characteristics truly muted by the distillation process? Or is it instead narrowed and focused? Certainly, in the pot still, I would argue that a lot of the collective character of ingredients and process up to that point are born beyond those fiery copper necks. I would argue that the greater hurdle for terroir character, and for site-specific distillery character, is wood. Wood is potentially the true agent of muting and obfuscation - if not necessarily total deletion. |

|

|

If you want to truly embrace terroir, you should really be embracing and using totally plain, refill, neutral wood. Wood should be as uniform and deferential to distillate as possible. As yet, no one has done this, probably because it would be commercially impossible. Terroir is a wonderful idea, but to truly put it into practice, to really cleave utterly close to the implications of the philosophy, would be an impracticality too far for most distilling businesses. What begins as a marketeer’s dream, becomes a salesperson’s nightmare at the business end. This is something evidenced by Waterford: noble ideas expressed in many, many good bottlings that were a challenge, ultimately, to sell. |

|

|

A final consideration about terroir, is the ‘people’ component. Ten years ago, I wrote this piece about whisky and terroir, with a particular focus on people. Broadly, I argued that whisky’s disconnection from the land over the 20th century, mirrored the distancing of Scottish people from their land. I think I still agree with what I wrote. It’s hard to dispute the idea that we are estranged from the physical land in which we live; the Scotland in which Scotch Whisky is made indisputably exerts less influence on the character of those whiskies than it did a century ago. |

|

|

Herein lies another challenge for embracing terroir in Scotch Whisky. We aren’t out physically tending the barley over the season, harvesting it by hand and then immediately commencing production. Ultimately, even if local barley is used, it’s a rather distant process: large scale, commercial, agricultural, industrial, broken up in odd chunks of time. Modern people are almost entirely disconnected from the land around them, and modern whisky production is often far removed from the individual human scale. Multiple layers of separation exist and must be overcome for terroir to start to ring true in Scotch Whisky, especially when compared with modern wine growing and making practice. |

|

|

|

|

|

To overcome these obstacles, to strip away these distances, we come back to conscious decision making. The frequently expensive and uncommercial deliberate decision making to force the land, the human workers and the method of manufacture into closer proximity in a manner which is clear and makes intellectual and technical sense. It’s a hard thing to do, to truly achieve this you have to pass through a minefield of potential gimmickry and come prepared to counter the pessimisms of your audience. One of terroir’s greatest stumbling blocks is the cynicism that confronts it. Ultimately – most critically - you also have to come up with something tangible and credible to show why it was worth it. |

|

|

I would argue that those obvious challenges surrounding its meaningful, and successful implementation in Scotch Whisky, are one of the strongest arguments for why it is a good idea. We live in age where there’s an abundance of whisky, more of the stuff than ever is bottled as single malt and there’s never been such a tyranny of choice or wide selection from which the drinker/collector can choose. The trouble is, so much of it is boring, the age of abundance is also the age of mediocrity. Any serious, quality-oriented, differentiated approach to breaking free of this mediocrity vortex is vital and to be lauded and supported. Terroir, in my view, is not about the obsessive, scientific burden of proof over whether and to what extent it exists; it’s a philosophy that provides useful approaches for modern whisky making and a means to produce characterful, distinctive, high-quality whiskies that stand necessarily apart from the masses. Yes, like all products, a commercial balance must be struck, they have to be correctly (often cleverly) marketed and sold, but it can provide a bedrock of something different and interesting that goes beyond the standardised modern malt whisky playbook. |

|

|

Ultimately, I would argue that achieving meaningful differentiation is going to become ever more important in the coming years. This past year, it has become utterly clear that Scotch Whisky is not in a happy place. I see it in my day-to-day work as an independent bottler, and I hear about it from colleagues across ever sector of the industry. There are going to be some very difficult years ahead for whisky and I believe authentic distinctiveness will become a great asset of durability for whisky businesses. In short: if you’re boring, you are more exposed. |

|

|

I think back to my trip to Orkney earlier this year and about what has happened in the intervening months. I’ve since heard that Scapa have been quietly buying up and distilling with a lot of Orkney Bere barley. I’ve had the chance to visit Brora and taste their very impressive new make. I’ve still yet to make it up to Glen Garioch to visit their post-refurbishment floor maltings and direct fired stills – but I think it’s telling that they did this. At time of writing, some of the larger industry players are starting to sell a lot more whisky at much cheaper prices. Things feel like they are changing quite quickly, and there are signs of admission through action from larger companies that things like quality, approach and pricing needed to change. |

|

|

Terroir is just one approach to making whisky, and not an easy one. It is one which provides a strong intellectual basis and set of approaches that, sensibly deployed, can deliver distinctiveness and quality. That’s why it’s interesting, that’s why it matters and that’s why I think it is important to give practitioners a chance and a hearing when they decide to go down that path. Ultimately though, while it is intellectually fascinating if a distillery business can demonstrate that their whisky expresses terroir, I believe it is of greater importance (for the industry and for the drinker) that it possesses high quality. The most successful pursuit of terroir is one that binds it together with quality. |

|

|

|

|

|

Orkney was something of an emotional trip for me. It was a trip we’d originally planned to take with my Dad. He had always wanted to see Orkney, but cancer and Covid had other ideas. In the end it took us five years after he passed away to make the journey up there. Life looks very different now, with two young children and so much having changed in those intervening years. Our kids had a wonderful time on Orkney. That confrontational awareness of the impermanence of all things that Orkney delivers, alongside the joyfulness and innocence of young children playing outside and becoming aware of nature, is a heady cosmic potion to consume. At night the wind would rally and tear about the cottage we were staying in, I would step out into that howling darkness until it stung. It is possible to understand in those moments why the farther flung parts of these Islands are called ‘thin’ places, where the distance between the living and the dead grows narrow to the point of perforation. It’s a place and feeling that can deliver an indescribable sense of calm. It’s also a physical situation and state of mind which makes the whisky in your glass taste so unbelievably fucking good. |

|

|

That would be my one final point about why terroir matters, feelings of relation and belonging to the land grant whisky an emotive power. Without that sense of emotional resonance, whisky is meaningless to me, just hot alcohol. My lifelong passion and love for this drink is underpinned by emotional ley lines of connection that lend it meaning. I am certain that’s the case for many of us. Those lines of connection can feel severed by mediocrity and modern whisky’s more vulgar traits, just as they can be invigorated by the beauty and social pleasures of this drink. The endeavour to make room for terroir in whisky, even just one firm root into the land, also creates space for these types of meaning, connection and emotion that clinically efficient manufacture can never hope to match. |

|

|

Angus MacRaild for Whiskyfun |

|

|

|

The Time Warp Sessions,

today’s indie Glen Moray span nearly 50 years |

It’s no secret, we love Glen Moray, and every chance to enjoy it is a golden opportunity. The brand played a major role over twenty years ago by offering whisky lovers a truly good single malt that was ‘a little cheaper than others’, but no less delicious! This time, we’re tasting two independent bottlings, one of which is quite rare and something we’ve always wanted to try. Today is the big day.

(Glen Moray was the main supplier of malt for Martin's blends, including the renowned VVO, which was very good - WF 84.) |

|

|

Glen Moray 17 yo 2007/2025 (53.1%, Murray McDavid, Benchmark, Kentucky bourbon barrels, casks #5844+48+51, 582 bottles)

Colour: pale gold. Nose: a whiff of very young chardonnay from a brand-new barrel right at first, then the whole thing falls neatly into place with orange sponge cake, ripe banana, vanilla cream, Golden Grahams, café latte and just a few cubes of mango thrown in for good measure. It’s simple, but that’s what makes it perfect. Light muesli. With water: a welcome touch of tension appears by way of some herbs and a few apple peelings. Mouth (neat): very, very good, creamy, with Lagunitas beer and banana-lemon cream. To tell the truth, this stuff is rather lethal... With water: lovely energy and brightness, citrus, passion fruit, vanilla, a trace of fresh oak, some quince jelly, and even a few jellybeans... Finish: good length, with a drop of acacia honey and a little chamomile. Nothing to add. Comments: strictly between us, one can’t help thinking of a very good young ex-bourbon Balvenie. And the Kentucky side of the barrels is clearly showing. Just joking.

SGP:641 - 87 points. |

|

Glen Moray Glenlivet 22 yo (58%, Moon Import, first series, sherry wood, 600 bottles, early 1980s)

No doubt a vintage from the very late 1950s or the very early 1960s, in the lineage of those magnificent official bottlings from thirty years ago. It’s important to remember that Moon, aka Sig. Mongiardino, was a true pioneer, alongside Silvano Samaroli and Eduardo Giaccone, including in the world of rum. Colour: gold. Nose: that combination of tobacco, chalk and dried fruits (including walnut) is absolutely splendid, and one gets the impression this came from a genuine old oloroso or amontillado ex-solera butt, or at the very least an ex-transport cask, with the wood itself having minimal impact—quite different from the feel of today’s casks made specifically for the whisky industry. In short, this is a dry sherry of stunning beauty, utterly classic, utterly elegant. With water: a touch more mineral now, with fresh cement, clay, and even a few fresh mint leaves... Mouth: magnificent, on tobacco, bitter oranges, mustard and walnut. With water: more of the same, plus some honeys, chestnut purée and black tea. It’s fairly compact, but that’s what makes it perfect. Finish: long, slightly more peppery, but with restraint. A touch of bouillon and miso soup in the aftertaste. Comments: not the faintest trace of OBE here, unless that slight stock cube note right at the end counts.

SGP:562 - 92 points. |

|

Serge's Non-Awards

2025 was another excellent year in terms of the quality of ‘enthusiast-grade’ whiskies worldwide, even if the economic figures weren’t particularly encouraging. Many distilleries from the rest of the world (ha) have made progress, and the Scots continue to produce great things, even though the trend of disguising malts with improbable casks hasn’t really slowed down—unlike the modest NAS whiskies, which seem to be a little less numerous. |

As for cognacs and armagnacs, small producers and independent bottlers are leading the way and seem to be winning over more and more whisky lovers—especially as they still cost two to three times less for equivalent quality. That said, malt whisky prices seem to be coming down. |

Favourite recent bottling |

|

|

Port Ellen 42 yo 1983/2025 (56.4%, OB, 200th Anniversary, 150 bottles)

WF 95

Port Ellen has consistently held first place year after year; in 2024, it was the 44-year-old ‘Gemini’ that won. Given the quality of certain older 10-year-olds—not to mention the famous ‘Queen’s Visit’—we are now looking forward to discovering the very first releases from the new Port Ellen distillery. |

|

|

Clynelish 24 yo (49.4%, Cadenhead, Sestante, +/-1989)

WF 98

The old Clynelish distillery, of course—though in a version that even the importer/bottler has deemed controversial. Legitimate or not, it remains our favourite, and that's not just for the sake of being contrary. |

Favourite bang for your buck |

|

|

Springbank 10 yo (46%, OB, +/-2024)

WF 91

Nothing more to add. Talisker 10 and Ardbeg 10 aren’t far off in this category. You have to turn to much older and more prestigious versions to match the incredible standard of these ‘entry-level’ whiskies that fear neither man nor beast.

|

|

|

Cuban Rum 76 yo 1948/2025 (48.9%, Chapter 7 Ltd, Spirit Library for Figee Fine Goods Switzerland, 108 bottles)

WF 95

To our great surprise, these very old pre-revolution Cuban rums—often offered at relatively reasonable prices—manage to hold their own against the stars of Jamaica, Guyana, or the finest agricoles. I hope there are still some left... |

|

|

Kimchangsoo ‘Gimpo - The First Edition 2024’ (50.1%, OB, South Korea)

WF 90

A magnificent little distillery that releases very few casks, but whose style and complexity—despite its young age—are truly impressive. We could of course also have included some Nordic producers here, along with a few other young distilleries around the world that are exceptionally deserving. |

|

|

A.H. Riise ‘Family Reserve Solera 1838’ (42%, OB, Virgin Islands, +/-2024)

WF 15

These insanely sweet sugar bombs—like certain Colombian rums or very liqueur-like ones from the Dominican Republic—really aren’t for us. Granted, using massive amounts of ice tones down the sickly-sweet effect on the palate, but here, we taste at room temperature. Go on then, you’re going to say it’s our fault… |

| |

January 2, 2026 |

|

|

|

Angus's Corner

From our correspondent and skilled taster Angus MacRaild in Scotland

Illustrations, Darius Pronowski

Whisky and terroir:

Part Two |

|

|

|

Terroir is a French concept, one evolved and nurtured over centuries. It describes the collective influence of soil, geology, climate, habitat and agricultural practice that collectively can be noticeably manifest in the final character of a product. Most commonly wine, but also other products as well. Terroir has also been argued to exist in people too, that regional characteristics related to the land and environment can be found in local populations as well. Finally, the most critical thing about terroir as it relates to French wine, is cumulative recognition and intellectual consensus arrived at over centuries of discussion and analysis. It is this latter point that Scotch Whisky lacks. We are just at the outset of that process in many ways, which is what makes our debates about this subject both healthy and necessary. |

|

|

I would characterise the modern ‘cultural’ era of whisky as aligning with the proliferation of the internet in the late 1990s. I would distinguish that from what we might define as a modern ‘production’ era, which is roughly from the early 1970s until today. In this modern cultural era, the people who pushed the discussion of terroir and made the case for it were Bruichladdich, chiefly Mark Reynier, who later further asserted this philosophy at Waterford. They were not the first people to talk about Scotch Whisky with language and ideas that alluded to concepts of terroir. Aeneas MacDonald’s book ‘Whisky’, published in 1930, expressed many viewpoints about Scotch Whisky which attributed its character to geographical influence. Indeed, this book is a fascinating artefact of an early, pre-modern era of specifically Scottish malt whisky enthusiasm. Malt whisky marketing from its fledgling era of the 1900s through to the 1980s, would frequently talk about water, glens, lochs, Highland air, Highland people, peat, tradition; things which are all potentially part of a much more formal definition of terroir. Ideas from wine were frequently repurposed for Scotch Whisky marketing, but rarely ever explicitly expressed. I remember being struck by the neck tag on an old 1970s bottle of Sherriff’s Bowmore that described it as ‘bone dry’ and ‘mineral’ – language very obviously re-purposed from wine. It was an approach which seems typical of Scotch Whisky: it would rather borrow and re-purpose, than create something bespoke. |

|

|

|

|

|

It was out of this world that Reynier and co took the next step and explicitly connected Scottish malt whisky with terroir. This was, at least in the initial phase, purely marketing, a way to speak about and sell a product which had been produced in a relatively unremarkable and traditional ‘modern’ manner with the destination of blended Scotch the intent. This is the most immediate ‘why’ of terroir in Scotch Whisky: a way to distinguish, to market and to sell a product that sets you apart from much larger, commercial competitors in a crowded marketplace. It is also one of the arguments that those who readily dismiss the existence of terroir in whisky reach for: it’s just marketing bullshit. It’s a useful argument as it reveals that, if you are going to talk about terroir, you’d better have something meaningful and demonstrable in your product and practice backing it up. |

|

|

Bruichladdich would go on, under Renier’s era, to make some valiant efforts in its production practices to shore up the terroir marketing angle. Under the ownership of Remy, Bruichladdich’s language has evolved and the explicitness around terroir has softened; focus on sustainability, provenance and ‘thought provocation’ have all been given equal or more prominent focus. Perhaps we can interpret this evolution as a quiet admission that such an intensely ideological focus on terroir is challenging to maintain to its logical conclusion. |

|

|

It is also often said that terroir is a choice, the wine grower can choose to step back and give it space, or she can choose to intervene to alter or delete its characteristics. It’s a tension between the natural effects of the land on a monoculture of vines and the judgement and human decision making of the wine grower. It is this idea of judgement and deliberate decision making that is most relevant and critical to Scotch Whisky as well. Terroir is bound up so deeply with French wine because it so often overlays effortlessly with the decisions which also lead to the greatest quality in the end product. The most lauded wines, also tend to vividly express terroir. In Scottish malt whisky production, can we say that the decision to pursue and allow room for terroir in the product are the same decisions that will lead to the finest possible quality whisky? I’m not convinced this is the case. |

|

|

|

|

|

When I was in Japan back in February, Yumi Yoshikawa at Chichibu made a very simple but important point: sometimes they use barley from Scotland, sometimes from Japan, but they don’t use Japanese barley for the sake of it as it isn’t always the best quality. They want the best quality barley for making whisky. A similar way to think about it might be a theoretical decision around what yeast strain to use. If you want to make a whisky that expresses terroir, you might want to isolate a unique yeast strain from your local barley, or from a peat bog you cut from, but will it make better whisky than using a more classical yeast? In whisky, terroir does not necessarily equal quality. |

|

|

So, does it follow that terroir in whisky is of less importance? That it belongs more to the remit of the marketeer and story spinners? I think it tells us that, if the whisky maker wants to legitimately discover, make space for and enshrine terroir in their product, then it must go hand in hand with quality as well. If you start a distillery with the foundational objective of expressing terroir, you will not really know the finer details of what character of whisky you’ll make, terroir is something that has to be discovered, then nurtured. Striking that balance while also navigating a pathway of decision making that elevates quality is a challenge. |

|

|

If done correctly though, it also conveys a potent message that goes beyond whisky and becomes political. True pursuit of terroir in whisky making is limiting, which means it limits the capacity of your business to endlessly expand and grow. To truly express character from your immediate and natural environment, means accepting limitations, it means standing apart from the mass commercial approach to whisky making that sacrifices quality in the pursuit of yield, efficiency and stretches credibility to breaking point on pricing. It says: I accept a different business model; I accept a certain limit to growth; I am pursuing commercial success via the route of quality and value - at the expense of volume. This is perhaps one of the most important reasons why terroir can matter, but it hinges on being done correctly with a rather dogmatic and ideological attention to detail. |

|

|